Stop the Zombie Trial: The "Kill Switch" for Failed Experiments

The most expensive decision in drug development (or product experimentation) is not starting a trial. It is continuing a zombie trial.

Imagine you are at the interim analysis of a Phase II study. You have enrolled 50 of 100 patients. You have spent $10 million. The data is... underwhelming. The p-value is 0.15. The effect size is half of what you pitched to the board.

Two voices speak up in the room:

- The Sunk Cost Optimist: "We designed this study to detect a 20% improvement. If the drug actually does that, and we just had bad luck in the first half, we still have a 60% chance of winning. Keep going!"

- The Hard-Nosed Realist: "But what if the drug doesn't do that? What if the true effect is exactly what we are seeing right now?"

The Optimist is relying on Conditional Power. They are calculating the future based on a "fixed" truth they hope exists.

The Realist needs Bayesian Predictive Power (BPP). They want to calculate the future based on the evidence they actually have.

Here is how to use BPP to stop pretending and start managing risk.

Evidence in the Wild: The Hydroxychloroquine "Kill Switch"

In 2020, the world was desperate for a COVID-19 cure. Hundreds of trials launched overnight. One of the most high-profile was the Coalition COVID-19 Brazil I trial, testing Hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) in hospitalized patients.

The Setup: They planned to enroll 600+ patients to see if HCQ improved clinical status.

The Interim: At the interim analysis, the data showed no clear benefit. The effect size was negligible.

In a traditional Frequentist setup, you might say: "The p-value isn't significant yet, but we haven't reached our sample size. Let's finish the trial to be sure."

The Bayesian Move:

The Data Safety Monitoring Board (DSMB) looked at the Predictive Power. They asked: "Given the data we have seen so far, what is the probability that HCQ yields a significant benefit if we continue to the full sample?"

The answer was devastating. The BPP calculation showed that to find a statistically significant difference (assuming the current trend held), they wouldn't need 600 patients. They would need >10,000 patients.

The Decision: The trial was stopped for futility immediately.

The Impact: This decision saved months of time, millions of dollars, and—most importantly—protected hundreds of future patients from being randomized to an ineffective drug with known cardiac side effects.

The Flaw of Conditional Power: The "What If" Game

To understand why Bayesian Predictive Power worked there, we have to look at the flaw in the standard alternative: Conditional Power (CP).

CP asks: "What is the probability of significance at the end, assuming the true treatment effect is X?"

The problem is X.

- The Trap: If you plug in the effect size you hoped for in the protocol (e.g., 20% benefit), you are calculating the probability of success in a fantasy world where your drug works perfectly, despite the data saying otherwise. This is how zombie trials survive.

The Solution: Bayesian Predictive Power (BPP)

Bayesian Predictive Power doesn't pick one version of the future. It simulates all of them.

Instead of asking, "What if the effect is 20%?", BPP asks:

"Given the data we have seen so far (and our prior beliefs), what is the probability that this trial wins?"

It acts like a weather forecast. It doesn't say "Assume the wind is North." It says, "Based on current pressure systems, here is the weighted probability of rain across all possible wind directions."

The Calculation Engine: A Walkthrough

Let’s look under the hood. Suppose you are testing a new landing page (or a cancer drug).

- Design: You need 100 samples to detect a 10% lift ($\delta=0.1$) with 80% power.

- Interim: At $N=50$, you observe a lift of only 2% ($\hat{\delta}=0.02$).

Step 1: The Prior (The Lens)

You start with a belief.

- Mathematical Definition: Let’s use a Skeptical Prior $\theta \sim N(0, 0.05^2)$. This assumes the effect is likely zero, and there is only a small probability (5%) that the effect is huge (>10%).

- Why? This forces the data to prove itself.

Step 2: The Update (The Posterior)

You combine the Prior with your Likelihood (observed data: 2% lift).

- The Posterior Distribution will now be centered somewhere between 0% and 2%—let’s say 1.5%.

- Crucially, the uncertainty around this 1.5% is quantified.

Step 3: The Simulation (The Integral)

The BPP calculator now runs a Monte Carlo simulation (10,000 runs):

- Draw a "True Effect" from the Posterior (e.g., maybe this run draws 1.8%).

- Simulate the remaining 50 patients assuming the effect is 1.8%.

- Check if the final combined dataset (100 patients) is significant ($p < 0.05$).

- Repeat 10,000 times.

The Result:

In this scenario, because the Posterior is centered at 1.5% (far below the required 10%), the BPP might come out to 8%.

- Translation: "There is only an 8% chance this experiment ends in a win."

💡Don't want to run the Monte Carlo simulation in Python?

I built a free Bayesian Predictive Power Calculator to do this heavy lifting for you. It runs the 10,000 simulations in your browser and gives you the "Kill Switch" probability instantly.

The Cross-Disciplinary Bridge: From Clinical to Tech

If you work in Tech (Optimizely, Netflix, Uber), you know this problem as "Peeking."

In A/B testing, engines like Optimizely use Sequential Probability Ratio Tests (SPRT). These are the Frequentist cousins of BPP. They create "boundaries" that allow you to stop early if the Z-score crosses a line.

The difference?

- SPRT (Tech): tells you "Is it significant right now?"

- BPP (Bayesian): tells you "Will it be significant in two weeks?"

For a Product Manager deciding whether to keep engineers working on a feature, BPP is often the more useful metric. It answers the resource allocation question: "Is this test worth finishing?"

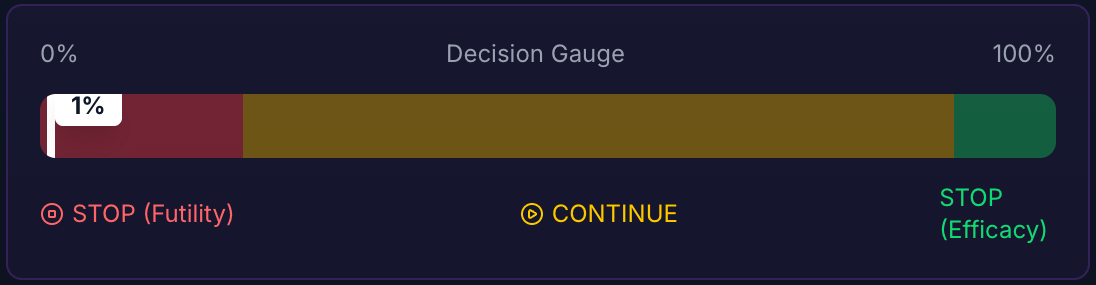

Decision Guidance: When to Stop

Once the engine runs, how do you use the number?

1. The "Futility" Zone ($PP < 10%$)

Decision: STOP.

Ethical Dimension: In clinical trials, continuing a trial with <10% BPP is arguably unethical. You are exposing patients to the risks of an experimental drug with almost zero probability that their participation will contribute to scientific knowledge.

Regulatory Note: While BPP is the "Eject Button" for failure, you cannot easily use it as the "Win Button" for success. The FDA usually requires rigid alpha-spending functions (like O’Brien-Fleming boundaries) to stop early for efficacy. You can stop for futility anytime; stopping for success requires permission.

2. The "Gray" Zone ($20% < PP < 80%$)

Decision: CONTINUE (or Adapt).

The Strategy: The jury is still out. This is where Sample Size Re-estimation comes in. If you are at 60% predictive power, can you increase the sample size to get to 80%?

3. Visualizing the Verdict: The Sensitivity Plot

Don't just show a number. Show the robustness.

- Red Line $\rightarrow$ Purple Line (Optimistic Prior)

- Blue Line $\rightarrow$ Green Line (Skeptical Prior)

- The "Kill" Signal: When both lines converge below 10%, the debate is over. The optimist and the skeptic agree.

Conclusion: Reality Check

Conditional Power asks, "If I were right, would I win?"

Bayesian Predictive Power asks, "Given what I see, will I win?"

In a high-stakes environment, the second question is the only one that matters. We use BPP not to be fancy with math, but to stop lying to ourselves about the sunk cost.

📬 Want more insights? Subscribe to the newsletter or explore the full archive of Evidence in the Wild for more deep dives into experimental design.

Member discussion