Inside the First FDA-Approved Bayesian Analysis

Last week, I wrote about the FDA's new Bayesian guidance covering what it says, what it doesn't, and the tension between Bayesian learning and regulatory pre-specification.

Guidance documents deal in principles. But what does an approved Bayesian analysis actually look like in practice?

The guidance cites REBYOTA as an example of acceptable external borrowing. This post unpacks what that actually meant: the model, the numbers, and the regulatory back‑and‑forth that ultimately got the analysis across the finish line.

Why REBYOTA matters

REBYOTA (fecal microbiota, live-jslm) was approved in November 2022 for preventing recurrence of Clostridioides difficile infection. That approval is notable for a specific reason: it was the first biologics license application where a Bayesian analysis served as the primary efficacy analysis.

Not a sensitivity analysis. Not a supportive analysis. The primary analysis.

Three years later, the FDA’s new Bayesian guidance explicitly cites REBYOTA as an example of acceptable Bayesian borrowing from prior trials. That makes it the closest thing we have to a regulatory template for what the agency is actually willing to approve.

The design problem REBYOTA solved

The Phase 3 trial (PUNCH CD3) faced a common challenge: the target population, patients with recurrent CDI, is relatively small, and placebo response rates are highly variable. A conventionally powered frequentist trial would have required either a much larger sample size or acceptance of substantial uncertainty.

The solution was to borrow information from their Phase 2b trial (PUNCH CD2) using a Bayesian hierarchical model.

The Phase 3 trial randomized 289 patients, with 267 receiving blinded treatment (2:1 randomization: 180 RBX2660, 87 placebo). The Phase 2b trial contributed an additional 82 patients from its 1-dose RBX2660 and placebo arms.

The distinction here matters. This was not pooling or combining data. The Bayesian model allowed information from Phase 2b to inform Phase 3 only to the extent the studies appeared compatible. Phase 3 data still dominated the inference.

The raw numbers

Using FDA‑recommended matched population definitions, the observed results were:

| Study | Arm | N | Successes | Rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PUNCH CD2 | Placebo | 43 | 19 | 44.2% |

| PUNCH CD2 | RBX2660 | 39 | 25 | 64.1% |

| PUNCH CD3 | Placebo | 85 | 53 | 62.4% |

| PUNCH CD3 | RBX2660 | 177 | 126 | 71.2% |

The challenge is obvious. Placebo response rates differed substantially between trials (44% vs 62%). Naively pooling these data would conflate fundamentally different baselines.

The Bayesian model addressed this by estimating study‑specific baseline rates, while borrowing information on the treatment effect across studies.

How dynamic borrowing works

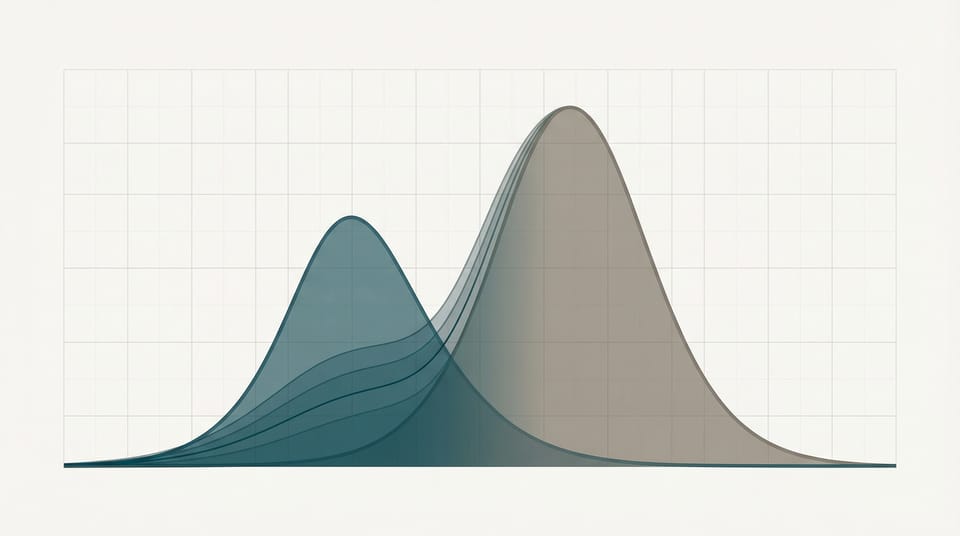

Treatment effects from each study were modeled as draws from a common distribution. The key parameter is τ (tau), the between-study standard deviation of treatment effects.

The intuition is straightforward:

- If treatment effects are similar across studies, the model estimates a small τ, leading to stronger borrowing.

- If treatment effects differ, the model estimates a larger τ, automatically down‑weighting external information.

This is why the borrowing is described as dynamic. The amount of borrowing is not fixed in advance; it is learned from the data.

In REBYOTA's case, the treatment effects were reasonably consistent (about 20 percentage points in Phase 2b, about 9 percentage points in Phase 3), so the model borrowed moderately.

The results FDA accepted

After FDA recommended aligning the population definitions between studies (applying PUNCH CD3's modified intent-to-treat criteria to PUNCH CD2), the final analysis showed:

| Metric | Value |

|---|---|

| Model-estimated placebo success | 57.5% |

| Model-estimated RBX2660 success | 70.6% |

| Treatment effect | 13.1 percentage points |

| 95% Credible Interval | [2.3%, 24.0%] |

| Posterior probability of superiority | 0.991 |

The pre-specified success threshold was a posterior probability exceeding 0.975 (equivalent to a one-sided α of 0.025). With a posterior probability of 0.991, the trial comfortably met its success threshold.

What FDA actually cared about

Reading the review documents makes the agency’s priorities clear.

Population alignment. FDA focused closely on exchangeability assumptions. Misaligned inclusion criteria triggered a requested re‑analysis. The numerical impact was modest (PP increased from 0.986 to 0.991), but the principle mattered.

Frequentist calibration. The success threshold was explicitly calibrated to Type I error. This approach, Bayesian inference with frequentist operating‑characteristic control, is now one of the three frameworks endorsed in the new guidance.

Sensitivity analyses. FDA required demonstration that conclusions were robust to alternative reasonable prior and borrowing assumptions. This expectation is now formalized in the guidance.

What this means for your next Bayesian submission

REBYOTA offers a concrete template for sponsors considering external borrowing:

- Pre‑specify everything. Priors, borrowing models, success thresholds, and sensitivity analyses must be locked in before unblinding.

- Align populations. If external data are not exchangeable, expect FDA scrutiny and re‑analysis.

- Calibrate success criteria. For pivotal trials, calibration to Type I error remains the least risky path.

- Demonstrate robustness. If conclusions hinge on a single prior choice, that is a problem.

- Engage FDA early. REBYOTA’s sponsor worked with FDA throughout development to align on assumptions and analysis plans.

The bigger picture

The January 2026 guidance isn't really about Bayesian methods per se. It's about efficiency. It's about using all available information, not just the current trial's data, to reach better decisions more quickly.

REBYOTA shows this can work in practice. A moderately-sized Phase 3 trial, augmented with Phase 2b data through principled borrowing, generated sufficient evidence for approval. The Bayesian approach didn't lower the bar. The success threshold was calibrated to the same Type I error rate as a frequentist test. It just used information more efficiently.

For rare diseases, pediatric extrapolation, and any setting where running large trials is impractical, this matters. The regulatory framework for Bayesian primary analyses now exists. REBYOTA proved it could work. The new guidance codifies what FDA learned from that experience.

The question isn't whether to use Bayesian methods. It's whether you're ready to use them well.

This post is a companion to The FDA's Bayesian Guidance: Learning in Theory, Pre-Specification in Practice, which covers the broader regulatory landscape.

I'm building tools to make regulatory-grade Bayesian calculations accessible to biostatisticians who don't want to write Stan code from scratch. If you're designing a trial with external borrowing, get in touch.

Member discussion